Table of Contents

- But Your Teeth are so Big, Grandma

- Peanuts

- Mandatory Arbitration

- Material Dividends

- Roger's Knows Full Well

Written January, 2007

Addendum: May 5, 2007: Note that Rogers was ordered to produce a figure for how many times the corporation has gone to arbitration since they introduced mandatory arbitration onto its consumer contract. How many times? Zero!! What does this say about the deterrent value of having that clause appear on the contract?

But Your Teeth are so Big, Grandma

Rogers was in front of the Supreme Court of Canada on December 14, 2006, defending the arbitration clause on its consumer contracts.

Rosalie Abella is a Supreme Court justice whose family law rulings in the Ontario Court of Appeal would lead you to anticipate that she'd be wary when a corporation as big as Rogers Wireless champions arbitration: her Court of Appeal rulings tended to be exquisitely sensitive to the vulnerabilities of the less powerful party in a divorce - typically, as it happens, the woman.

However, as we watched Rogers defend its clauses in the Supreme Court of Canada, she intervened with a question for the plaintiff, Muroff, shaking her head as though there was something she was missing: "Isn't arbitration a good thing?" she asked the plaintiff's lawyer. "Litigating disputes in court is costly; the delays of getting to trial are notorious. Arbitration allows the parties to expedite a dispute and to craft a settlement that's more particular to their needs. Are you really saying that it's inherently a bad thing that consumer disputes be resolved through arbitration?"

Perhaps it was rhetorical question. The ruling has not come down yet (as of January 7, 2007 - (as of May 5, 2007)) and will be delayed by the court's request of the parties to submit additional arguments in light of the fact that the Quebec National Assembly passed legislation (on the very day that Rogers was in the Supreme Court, as it happens) that prohibits arbitration clauses on consumer contracts. We don't know yet what is really on (and in) Abella's mind.

Perhaps Abella was prodding the plaintiff to speak more emphatically to the cynicism of Rogers in clothing itself with an institution often regarded as a lamb-like alternative to the cut throat infamies of the adversarial system.

Perhaps Abella was being coy.

What, after all, is the problem with arbitration? Don't we all need teeth to eat?

Peanuts Back to Top

My legal dispute against Rogers is in Small Claims Court. Let’s be frank though. Small Claims Court is small potatoes.

There’s a limit on the kinds of damages a Defendant can be sued for in Small Claims Court. It’s currently set at $10,000 in Ontario. The majority of Small Claims Court damages are, in any event, for the more mundane kinds of sums that humble a $10,000 claim, making it look like wanna-be class.

Small claims court cases are as annoying to Rogers as mosquitos in summer, the occasional case of West Nile excluded.

…Much punier of course – say along the order of mosquitoes in February – since Rogers attempted to preclude, across Canada, the ordinary consumer from resolving any legal dispute with Rogers in Small Claims Court.

But let’s admit it. Small Claims Court – glorious plebian venue that it can sometimes be – doesn’t generate the type of trouble that Rogers was trying to exterminate with its binding arbitration clause.

Rogers’ real bogey, it’s terrifying pursuer – the thing that makes Rogers tremble in bed at night with the doors and windows locked and sealed – is the class action law suit.

It was the class action law suit that made Rogers Legal Department hunker down to the drafting table and come up with its mandatory arbitration clause.

Mandatory ArbitrationBack to Top

Rogers has a clause on its contract that supposedly binds Rogers’ consumers to arbitration in the event of a legal dispute. That clause stipulates the following:

Arbitration

34. Any claim, dispute or controversy (whether in contract or tort, pursuant to statute or regulation, or otherwise, and whether pre-existing, present or future) arising out of or relating to: (a) this agreement; (b) the services or equipment provided to you by us; (c) oral or written statements, or advertisements or promotions relating to this agreement or to the services or equipment; or (d) the relationships that result from this agreement (collectively the “Claim”) will be determined by arbitration to the exclusion of the courts. You agree to waive any right you may have to commence or participate in any class action against us related to any Claim and, where applicable, you also agree to opt out of any class proceeding against us. Please give notices of any Claims to: Legal Department, 333 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario M4W 1G9. Arbitration will be conducted by one arbitrator pursuant to the laws and rules relating to commercial arbitration in the province in which you reside that are in effect on the date of the notice.

The arbitration clause in Rogers’ contract precludes consumers from going to court period, thereby eliminating the two standard venues in which the ordinary consumer most typically seeks justice: small claims court, and class action.

The arbitration clause commits the consumer to hire an arbitrator to resolve any legal disputes that arise with Rogers. The going rate for commercial arbitrators is approximately $4,000 per day – a cost that needs to be paid upfront and is split in two between plaintiffs and defendants. That figure doesn’t include what a plaintiff would spend on legal counsel.

For the vast majority of consumers (almost certainly all of those whose damages are less that $2,000) this clause - if it were enforceable – would operate as an insurmountable deterrent to seeking a legal remedy; or indeed even to defending oneself against a legal claim made by Rogers.

Arbitration clauses in consumer contracts began to be introduced across Canada in the last several years as class action law suits have taken off as a way for consumers to get redress from large corporations with deep pockets and resources for a prolonged legal battle. The procedure and legal fee arrangements of class action law suits account for the fact that the costs of litigation in Canada can be astronomical, particularly for ordinary consumers.

One goal behind the introduction of class action law suits into Canadian law was to provide consumers with "individually non-viable claims" - that is, claims that might not otherwise be pursued because the amounts at stake are small compared to the cost of litigation - to group their claims together with other plaintiffs. Most class action law suits work on the basis of a contingency fee for the class members' lawyer; that is, lawyers for the class take on all of the risks and costs of the case and if the case does not succeed, then the class members pay nothing. If the case succeeds, the lawyers for the class are paid a percentage (the contingency fee) of the damages.

A second goal of class action law suits is judicial economy. These suits allow for plaintiffs, and the courts, to avoid duplication in fact finding and legal analysis that would be required if each plaintiff had to individually litigate their cases.

The third goal of class action law suits is behaviour modification. In a climate where governments have de-regulated industries, class action law suits operate as a deterrent against powerful wrongdoers behaving cavalierly towards consumer and citizen interests in the certainty that most ordinary consumers do not have the resources to pursue them in law. The ominous potential for corporations of a costly class action law suit, with a substantial damage award to a large group of class members and the attendant negative publicity, reduces the incentive of large corporations to do a crass cost benefit analysis putting profit ahead of consumer and citizen interests.

Class action lawyers on the plaintiff's side operate simultaneously as entrepreneurs (some corporation-side lawyers might say "predators" preying upon the fragile and vulnerable corporation) and also as private attorneys general - keeping the corporation in line with the laws of state. Contingency fees provide them with an economic incentive to pursue powerful corporations and force them to comply with the law.

As class action law suits in Canada have only really been taking off in the last 10 years, major corporations have been seeking ways to reduce their risks. One of the mechanisms that the legal departments of major corporations have been proposing is the introduction of arbitration clauses into consumer contracts. These clauses contractually preclude the consumer from suing for damages in a class action law suit, theoretically eliminating the corporation's vulnerability to the costs of a class action.

Increasingly, courts are finding that these clauses are unconscionable and should not be enforced. And legislatures, such as Ontario's, have passed legislation that renders the clauses unenforceable.

Canadian jurists are increasingly recognizing that arbitration clauses on consumer contracts are prejudicial to the interests of ordinary consumers and unevenly stacked to insulate large corporations from precisely the kinds of law suits that governments sanctioned to stimulate corporations to comply with both law and fundamental equity. Consumer advocacy groups have started to agitate for legislation that would preclude such a cynical corporate use of the alternative dispute mechanism of arbitration. For example, the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) - a non-profit organization that provides legal and research services on behalf of consumer interests (in particular, vulnerable consumer interests) - has written a report that investigates the history and corporate use of arbitration clauses and strongly recommends that provinces introduce legislative changes that will prohibit the use of mandatory arbitration clauses and protect consumers’ right to voluntarily choose a range of dispute settlement mechanisms in their dealings with businesses, whether arbitration, small claims court or class actions.

The report indicates that provincial governments like Ontario, and individual courts across the country, have started to compel corporations to behave like decent corporate citizens by rendering those clauses unenforceable through Consumer Protection legislation, or by refusing to uphold arbitration clauses in court on the grounds of unconsionability. PIAC also acts as an intervener representing consumers in cases where consumer interests are at stake.

Apart from inoculating the corporation from the damage that a class action law suit can do to a major corporation (at the expense of the consumer's better interests and litigation rights), there are other corporate interests that are served by inserting arbitration clauses into consumer contracts. These interests very often go against the public interest in having matters proceed to a trial.

The PIAC report goes over some of the classical asymmetries of power between corporations and consumers that skew the playing field of a consumer arbitration in an unseemly manner. The report gives nine reasons why mandatory arbitration clauses are bad for consumers:

PIAC's Assessment of "Grandma's" Teeth

Class Actions: The Way of the Dodo Bird?

Mandatory arbitration clauses on consumer contracts didn't come out of thin air. They originally arose in the United States out of the ongoing and ever-mutating battle between corporate and plaintiff-side lawyers. Myriam Gilles, an American law professor writing in the Michigan Law Review in December 2005, indicates that the corporate lawyers appear to be winning; and they are doing so by injecting the self-same class action waivers that Rogers uses in tandem with the demure and alluring arbitration provisions that appeared to have so lulled Justice Abella.

As Gilles writes in "Opting out of Liability: The Forthcoming, Near-Total Demise of the Modern Class Action", a handful of aggressive corporations with a keen interest in avoiding class action liability introduced waivers like Rogers' that are poised to "metastasize throughout the body of corporate America and bar the majority of class actions as we know them."

Gilles projection for one of the classic American recourses of oppressed consumers - the class action law suit - has ominous implications for consumers rights in Canada:

I regard it as inevitable that firms will ultimately act in their economic best interests, and those interests dictate that virtually all companies will opt out of exposure to class action liability. Why wouldn't they? Once the waivers gain broader acceptance and recognition, it will become malpractice for corporate counsel not to include such clauses in consumer and other class-action-prone contracts.

So far, Canada appears to be quietly asserting for itself a different balance between raw corporate power and the masses of vulnerable consumers exposed to what Gilles calls "the evolutionary arms race that is afoot between entrenched corporate interests and entrepreneurial plaintiff's lawyers." Two provinces, Quebec and Ontario, have already passed strong consumer protection legislation that emphatically precludes mandatory arbitration clauses on consumer contracts, and BC has opted to neutralize them judicially.

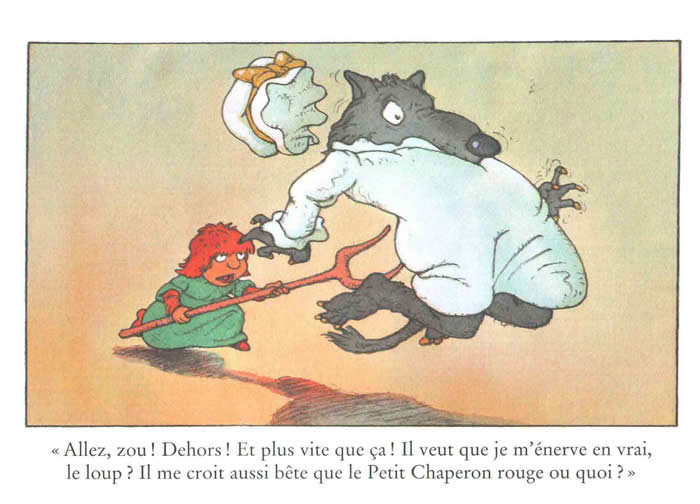

Canadians seem to be a bit more savy and worldly wise than our American cousins, with their hapless faith in the corrective force of the free market. The Canadian response to the clauses, on a province-by-province basis, has apparently been more shrewdly suspicious than the American, less Little Red Riding Hood and more Little Miss Run-For-Your-Lives. Canadians seem to be prepared to say:

“Give me a break Mr. Wolf. Do you really think I don’t know how to tell the difference between a wolf and a grandmother? Come on. Up you get! Out you go!”

“Allez, zou! OUT! And get a move on! Do you want me to get pissed off for real Mr. Wolf. Who do you take me for? Little Red Riding Hood or something?”

It remains to be seen whether the Supreme Court of Canada picks up on the randy little spirit of righteous indignation and rebellion that lurks within the Canadian soul, a spirit that appears to be quietly, but infectiously, embracing provincial legislatures. As of early May, 2007, the Supreme Court has not yet shown its cards on who it is rooting for: the miserable little creature that Justice Abella found in the snow, dying of cold and hunger, or the audacious little brat that's nobody's fool.